For the last century, automotive engineering has followed a strict rule of segregation: the chassis carries the load, the engine provides the power, and the fuel tank holds the energy. These components were distinct, separate, and heavy.

When we entered the Electric Vehicle (EV) era, we didn’t change this rule; we just swapped the components. We replaced the gas tank with a lithium-ion battery pack. But this created a new problem, one that engineers call “parasitic weight.”

To get more range, you need a bigger battery. A bigger battery adds weight. To carry that extra weight, you need a stronger (and heavier) chassis and bigger brakes. This creates a vicious cycle where the car spends a significant amount of its energy just hauling its own power source around. A Tesla Model S battery pack, for instance, weighs roughly 1,200 pounds—essentially a grand piano strapped to the underside of the car.

But what if the battery didn’t have to be a passenger? What if the battery was the car?

This is the promise of “Structural Power,” a technology that aims to turn the very body of the vehicle—the roof, the doors, the hood—into an energy storage device.

The Dual Life of Carbon Fiber

The secret to this alchemy lies in the atomic structure of carbon fiber. For decades, we have prized carbon fiber for its mechanical properties: it is stiff, light, and strong. But carbon has another property that automotive engineers largely ignored until recently: it is electrically conductive.

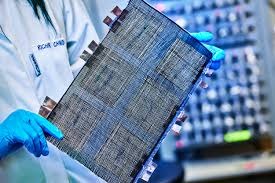

Researchers at institutions like Chalmers University of Technology have demonstrated that carbon fibers can perform two jobs simultaneously.

- The Skeleton: They can act as the load-bearing reinforcement material, providing the stiffness required to meet crash safety standards.

- The Electrode: They can act as the negative electrode (anode) in a lithium-ion battery, hosting lithium ions within their microstructure.

By sandwiching a glass-fiber separator (which insulates the electronics but transfers the load) and a positive electrode between layers of carbon fiber, and then infusing the whole stack with a specialized structural electrolyte resin, you create a material that is hard as steel but stores electricity like a battery.

The Concept of “Massless” Energy

The genius of this approach is what scientists call “massless energy storage.”

Obviously, the material still has mass. But because the battery is replacing a structural component that had to be there anyway (like the roof), the “battery weight” is effectively zero. You aren’t adding a battery; you are functionally deleting the dead weight of the traditional chassis.

If you can replace the steel roof, the aluminum door panels, and the plastic floor of a car with structural energy storage, you can theoretically reduce the weight of an EV by up to 50%. A lighter car requires less energy to move, which means you need less storage capacity to achieve the same range, creating a virtuous cycle of efficiency that the current “skateboard” battery platform can never achieve.

The Engineering Hurdles

If the physics works, why aren’t we driving battery-cars yet? The challenge is the “Trade-Off Triangle.”

In material science, you usually have to choose between stiffness (mechanical performance) and energy density (electrochemical performance).

- Carbon fibers that are good at storing ions tend to be structurally weaker.

- Carbon fibers that are incredibly stiff tend to be poor at storing ions.

Finding the “Goldilocks” fiber—one that is strong enough to survive a highway crash but conductive enough to power a motor—has been a decade-long struggle. Early prototypes were either too weak to build a car with or had such poor battery life they weren’t worth the cost.

However, recent breakthroughs in 2024 and 2025 have produced structural cells with an energy density of 30 Wh/kg. While this is lower than a standard Tesla cell (approx. 250 Wh/kg), remember the math: you don’t need to match the density of a standard battery if you are eliminating thousands of pounds of structural dead weight.

The Safety Question

The final frontier is safety. In a traditional EV, the battery is buried deep in the floor, armored against impact. In a structural power vehicle, the battery is the impact zone.

If you get T-boned in a car where the door is a battery, what happens? Does it catch fire? Is the passenger sitting inside a potential short circuit?

Developing electrolytes that are non-flammable and resin systems that fail gracefully (without thermal runaway) is the current focus of the industry. The goal is to create a material that, when cracked, simply stops working electrically rather than exploding.

Conclusion

We are witnessing the end of the “component” era of car building. The future is integration. Just as biology doesn’t separate our bones from our blood supply (our marrow creates our blood), the next generation of vehicles will blur the line between structure and fuel.

While we may be a few years away from a fully structural sedan, the technology is already trickling into drones and consumer electronics. It is an inevitable evolution. By unlocking the electrochemical potential of automotive composites, engineers are not just making cars lighter; they are changing the fundamental definition of what a vehicle is made of.